Deep Dive: Food Apartheid

Despite the intimate relationship many of us have with various components of the food system, the vast network of players that make it up are often heavily intertwined and complex, and can result in huge inequalities between those that it’s meant to serve.The concept of a “food desert” is often used to describe neighborhoods/communities where access to nutritional foods is significantly limited. “Access” can be broadly defined but usually is assessed using data regarding distance from grocery stores, availability of public transportation, average food prices, and nutritional value of available foods. This term, “food desert”, is often rejected by those working for food justice, as the word “desert” implies that this phenomenon is naturally occurring. Another phrase, “food apartheid” is preferred by many, as it considers the human aspect of this condition, namely the conscious and oppressive nature of it. This term considers that communities that lack adequate access to nutritional foods lack this access due to commercial, governmental, and social intervention that have actively excluded them. This term also counteracts many social associations with the word “desert”. In an interview regarding food apartheid and racial inequality, Karen Washington, a political activist and community organizer sheds light on issues with the term:

“Who in my actual neighborhood has deemed that we live in a food desert? Number one, people will tell you that they do have food. Number two, people in the hood have never used that term. It’s an outsider term. “Desert” also makes us think of an empty, absolutely desolate place. But when we’re talking about these places, there is so much life and vibrancy and potential. Using that word runs the risk of preventing us from seeing all of those things.”

So, what does food apartheid look like? It varies across the country and across the world, but in many cases, it can be as simple as being a mile or more from a supermarket (or other grocer with a reasonable variety of nutritious and diverse food options). While that may sound insignificant to some, this distance (which we remind you is at the lower bound) can essentially inhibit access to individuals and families who don’t have access to required modes of transportation and can’t afford the required time to make that trip regularly (in 2015, 6.5% of white households didn’t have reliable access to a car while 19.71 percent of Black households did not have access to a car). This is typically paired with local small-scale grocers that thus only offer a small variety of nutritious foods at a premium that puts them out of the price range of many low income individuals and families. This lack of reasonable access can have serious health implications (such as diabetes, obesity, and heart disease) which can serve as significant deterrent to economic mobility.

How does this happen? There are a number of ways this scenario materializes. Work from the Racial Justice Project at the New York Law School offers a simplified system of mechanisms that can compound to cause food apartheid. These mechanisms include residential segregation, “commercial flight from urban communities,” “continued supermarket scarcity in urban communities,” and “victim blaming”. Residential segregation is often the result of government policies that influence zoning regulations, redlining, and the power of race-discriminatory mortgage programs that thus determine the make-up of various neighborhoods and communities. “Commercial flight from urban communities” results when commercial grocers are often incentivized by government subsidized loans to move closer to wealthy suburbs, as well as the ease of operation that comes with serving communities of a largely homogeneous ethnic/cultural makeup. “Continued supermarket scarcity in urban communities” is due to a variety of legal hoops that have accumulated over time to make urban locations more costly for larger grocers. And “victim blaming” occurs when policy makers blame minority communities and low-income communities for lacking adequate decision making skills regarding their purchasing choices—policy makers often blame individuals for purchasing non-nutritious foods instead of admitting they’ve helped create a system that’s failing its people. Additionally, while “urban revitalization” programs work to improve living conditions in urban communities, this “revitalization” is typically met with rampant gentrification that only works to displace minority and low-income populations. What’s more, most communities living in a food apartheid are flooded with easily accessible and highly marketed fastfood chains which offer low-cost and low-nutrition food options in the face of far more distant and costly options. Mechanisms like these have worked to not only oppress minority and low-income communities, but to reinforce the systems that sustain this oppression for generations.

Our food system is not a natural phenomenon, but rather, the result of strategic policy decisions that often put profit and power above sustainability and equity. Local communities are deeply affected by racist and discriminatory contracts, policy makers, supermarket chains, and real estate corporations. As we mentioned before, “food desert” is a term often used by analysts, media, and others, to define areas on a map, but it neglects the fact that real people live there and experience real oppression as a result of others’ decisions. Food apartheid more accurately describes the systemic injustice/neglect that results in unequal access to nutritious, affordable food between neighborhoods within the same cities. As participants in our food system and advocates for policy change, we can take steps to support individuals and organizations that are doing work to make change in areas effected by food apartheid.

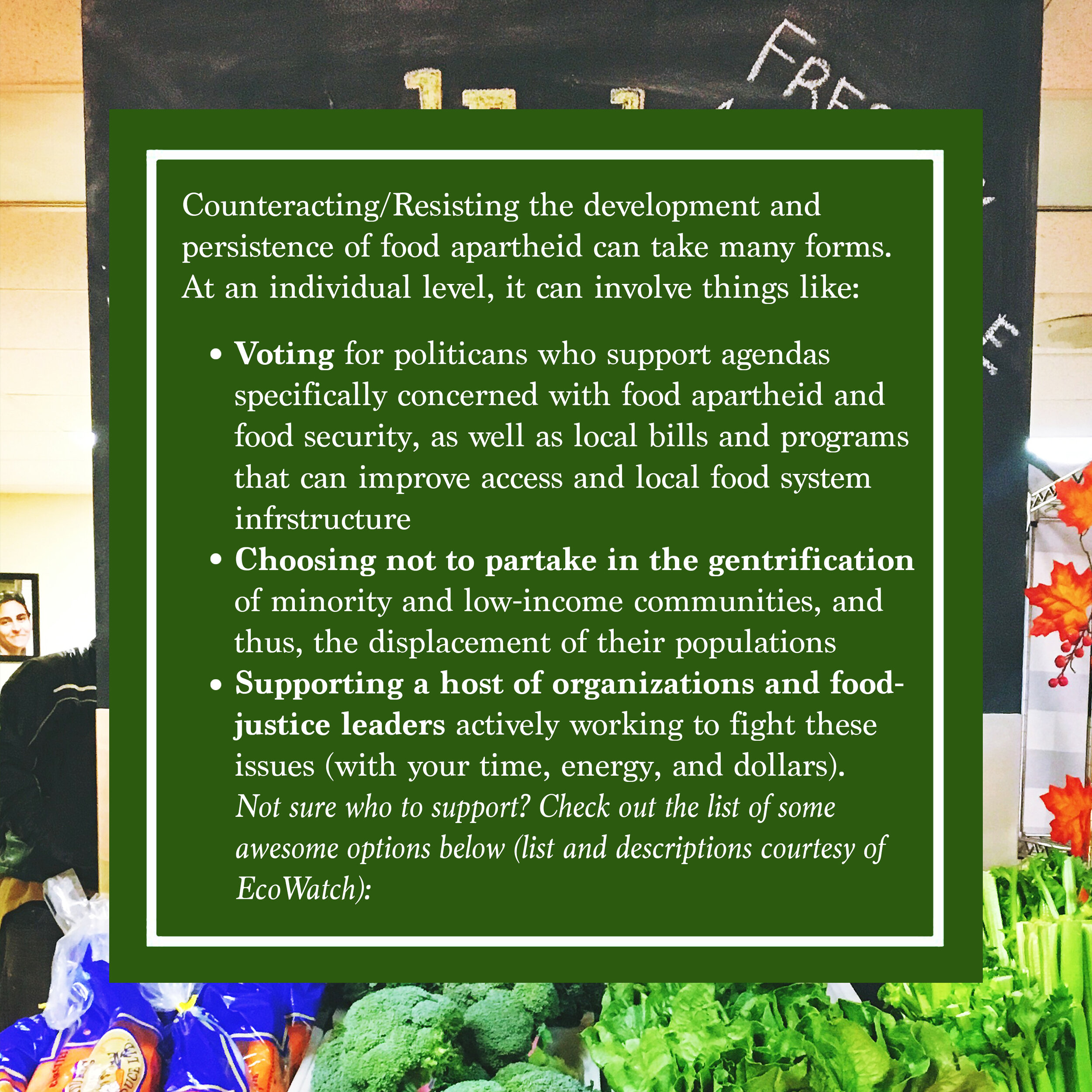

A Food Access Market at The Stop in Toronto, Canada

Counteracting/Resisting the development and persistence of food apartheid can take many forms. At an individual level, it can involve things like:

Voting for politicans who support agendas specifically concerned with food apartheid and food security, as well as local bills and programs that can improve access and local food system infrstructure

Choosing not to partake in the gentrification of minority and low-income communities, and thus, the displacement of their populations

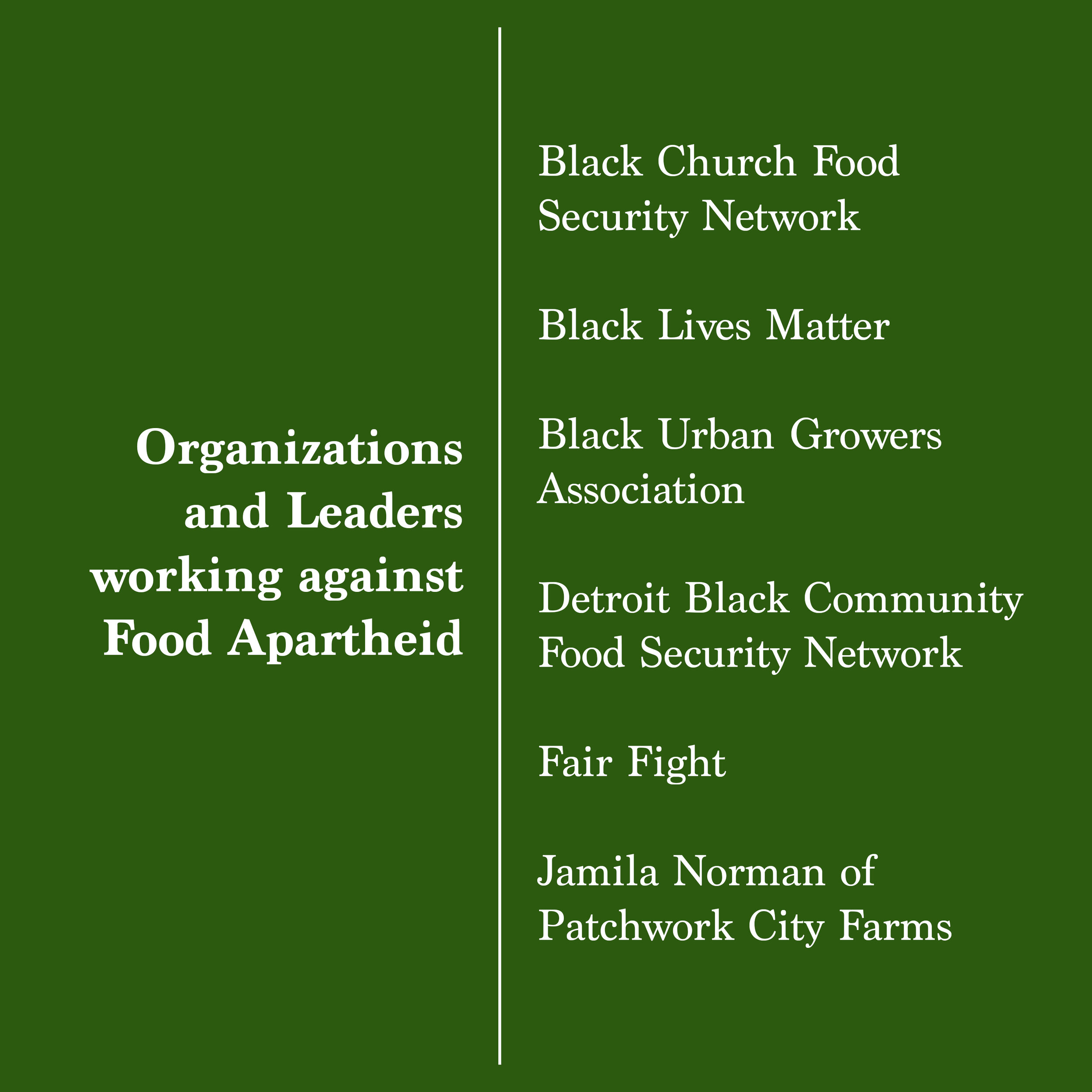

Supporting a host of organizations and food-justice leaders actively working to fight these issues (with your time, energy, and dollars). Not sure who to support? Check out the list of some awesome options below (list and descriptions courtesy of EcoWatch):

Black Church Food Security Network

Based in Baltimore but operating nationally, the Black Church Food Security Network aims to support gardening and farming within Black churches. They establish agricultural projects on church land, connect farmers to congregational markets, and create asset maps of Black churches and surrounding neighborhoods to help better use resources. They also operate a small directory and interactive map of faith-based Black farmers across the East Coast, Midwest, and southeastern U.S.

Black Lives Matter, a movement created in response to murders of innocent Black people by police and vigilantes, works to build power to bring justice, healing, and freedom to Black people across the globe. Black Lives Matter is a broad coalition and affirms the lives of Black people across the gender spectrum, of all abilities, and of any documentation status.

Black Urban Growers Association

Black Urban Growers maintains a network and community support in order to foster Black leadership in food and farm advocacy. Their programs include the Black Farmers & Urban Gardeners Conference, a national conference started in 2010 that brings together Black farmers, advocates, chefs, and communities to share their best practices and leadership efforts.

Detroit Black Community Food Security Network

The Detroit Black Community Food Security Network is working on the ground in Detroit, Michigan, to ensure that the local urban agriculture movement is racially and socially inclusive. It was founded in 2006 to mobilize the Black community to address food insecurity challenges, and the network believes that the most effective movements grow organically within the communities they are designed to benefit. They operate organic urban farm sites, various local food policy initiatives, and a cooperative food-buying program for community residents.

One of the most impactful ways to participate in democracy is by voting, but many people, particularly in minority communities, face structural barriers against having their voices be heard. Fair Fight was founded by Stacey Abrams, who lost a close race for Georgia governor in 2018 amid allegations that her opponent, then-state Secretary of State Brian Kemp, had engaged in voter suppression. The organization aims to end voter suppression, make sure everyone can access their constitutional right to vote, and fight for fairer elections. You can donate online here.

Jamila Norman of Patchwork City Farms

Based in Atlanta, Georgia, Jamila Norman is a world-renowned urban farmer and food activist. In 2010, Norman founded Patchwork City Farms, a certified naturally grown organic urban farm where Norman farms—and provides the local community with safe and nutritious foods. Norman is also co-founder of EAT Where You Are, an initiative that aims to spread awareness of the importance of including fresh foods in diets, and is the manager and one of the founding members of the South West Atlanta Growers Cooperative, which helps Black farmers create equitable, sustainable, responsible food systems.

Karen Washington, founder of Rise and Root Farm

Karen Washington, a farmer and community activist, wants to build a different agricultural narrative, inclusive of all races, genders, and sexualities. She created Rise and Root Farm to be a place of healing for diverse and marginalized communities—particularly important today, as black farmers work to call attention to not only their own contributions to the modern food system but also the impact of the slave trade on the development of global food chains. "Agriculture must be inclusive in its diversity," Washington tells Food Tank.

National Black Food and Justice Alliance

A coalition of Black-led organizations, the National Black Food and Justice Alliance builds Black self-determination around food and land sovereignty. They accomplish this through community organizing and increasing visibility of Black narratives, visions, and achievements. In 2018, co-founder Dara Cooper was honored with a James Beard Foundation Leadership Award "for dedicating her life to racial equity and justice in the food system and increasing capacity and visibility of Black-led narratives and work."

A Minneapolis-based organization, Reclaim the Block works to reallocate city money away from police and instead toward community-led health and safety initiatives. They have assembled an extensive digital toolkit to help communities in all cities and states advocate for divestiture from police. You can support them via donations or by signing their petition encouraging the Minneapolis City Council to redirect police department funding toward resources for Black and Indigenous communities.

Based in Philadelphia, Soil Generation is a Black- and Brown-led coalition with a vision for "a people's agroecology"—a combination of environmental and food justice with a focus on community self-representation, anti-racism training, education, and advocacy. Soil Generation has successfully worked with the city council to amend a bill that would have put urban gardens at risk and continues to actively campaign for rights to vacant lots.

Tanya Fields of the Black Feminist Project

As founder and executive director of The Black Feminist Project, Tanya Fields is a food justice activist and educator. Fields started the Libertad Urban Farm, an organic urban garden in the Bronx, as an effort to address the lack of nutritious food and food education accessible to low-income people, specifically underserved women of color. Additionally, Fields works closely with The Hunts Point Farm Share, connecting city residents to high-quality local produce through community-supported agriculture.

Toni Tipton-Martin, based in Baltimore, Maryland, works on a series of endeavors to promote food justice. She has written two James Beard Award-winning books that trace Black cuisine, Jubilee and The Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbook. Martin served as the president of Southern Foodways Alliance board of directors and was the first Black food editor at the Cleveland Plain Dealer. Additionally, Martin founded the SANDE Youth Project, a nonprofit organization that works with children to combat obesity while supporting Black food culture.

The Urban Growers Collective operates eight urban farms on 11 acres of land in Chicago's South Side and works with more than 33 partner organizations to create economic opportunity and boost healthy food access. Each farm uses organic methods and integrates education, leadership training, and food production. The organization was co-founded by Laurell Sims and Erika Allen, a visual artist and food advocate who works to use creativity for social change.

Sources:

Anguelovski, I. (2016). Healthy food stores, greenlining and food gentrification: Contesting new forms of privilege, displacement, and locally unwanted land uses in racially mixed neighborhoods. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 39(6), 1209-1230. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12299 Explains how urban environmental justice is at a critical juncture in its trajectory when outside investors start to value and re-invest in marginalized neighborhoods.

Barker, C., Francois, A., Goodman, R., & Hussain, E. (2012). Unshared bounty: How structural racism contributes to the creation and persistence of food deserts. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/racial_ justice_project/3/ Analyzes the dimensions of structural racism that create and sustain areas of limited access to healthy food in low-income communities.

Brones, Anna (2018). Food apartheid: the root of the problem with America's groceries, Interview with Karen Washington. The Guardian. Published 15 May 2018. Accessed 23 June 2020 via: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/may/15/food-apartheid-food-deserts-racism-inequality-america-karen-washington-interview

Penniman, Leah. Excerpt from Farming While Black from Soul Fire Farm. Accessed 23 June 2020 via: https://www.chelseagreen.com/2018/how-to-end-a-food-apartheid/

Schupp, J, (2019). Wish you were here? The prevalence of farmers markets in food deserts: An examination of the United States. Food, Culture & Society, 22(1), 111-130. https://doi.org/10.1080/15528014.2018.1549467 Shows that although farmers markets are commonly recommended solutions to increasing access to fresh foods in areas labeled as “food deserts,” in actuality farmers markets rarely operate within such food deserts thus making them relatively ineffective for this purpose.