Perennial Plants for Soil Health

This article was written by a guest contributor, Laura Daniel. Read about Laura here.

What are Perennials?

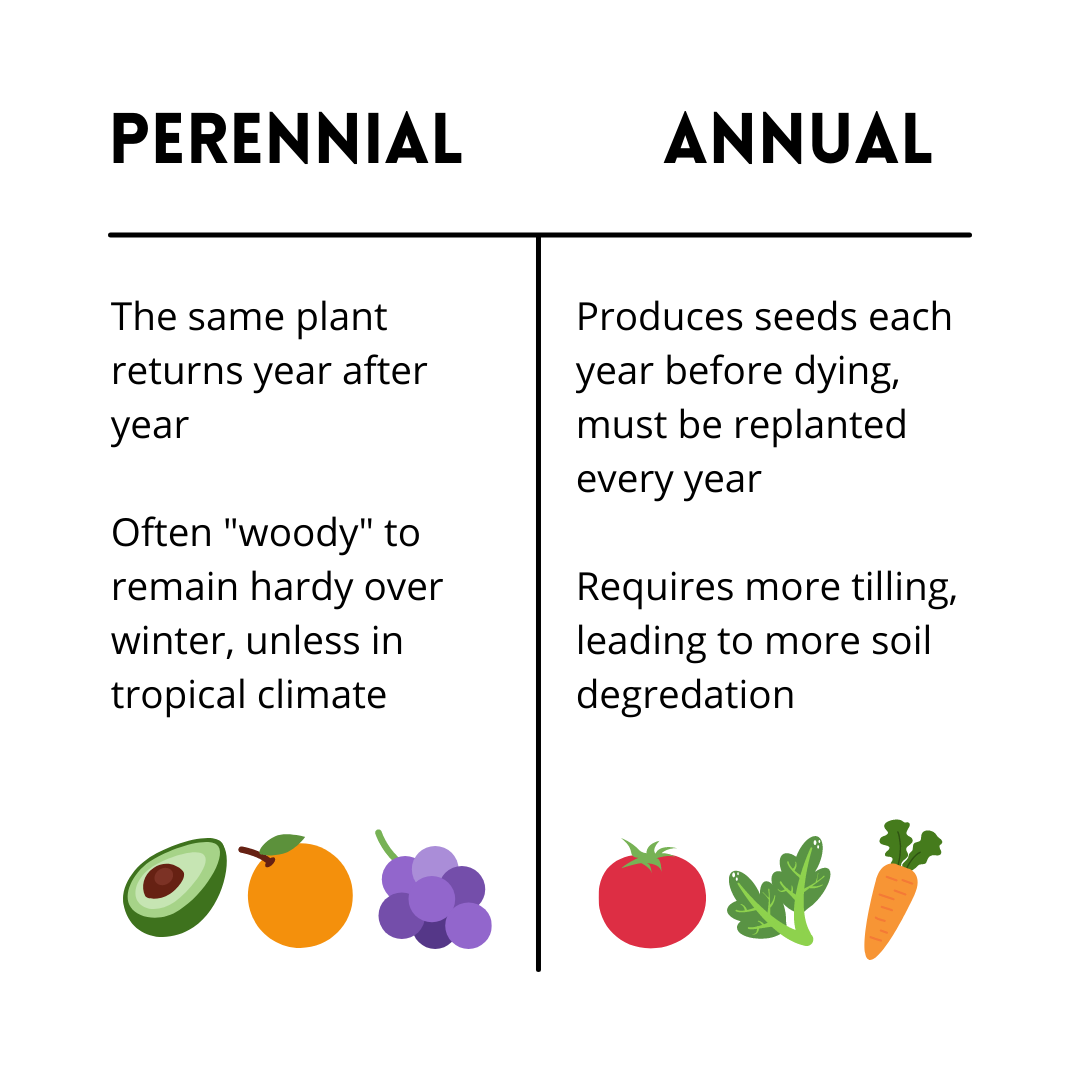

While many of us might not know the difference between an “annual” plant and a “perennial plant”, the core differences are likely more familiar than you think. Most of us know there are some plants whose seeds you have to plant every year—lettuce, tomatoes, daisies—and others that survive the winter and come back year after year—apple trees, rose bushes. I remember as a kid my mom would buy annuals for our front yard because they’re beautiful and bright, even though their beauty would only last one growing season. Perennials on the other hand, offer the benefit of blooming year after year without reseeding.

The Advantage of Perennials

The real advantage of perennials comes from what you can’t see—their roots! Perennial crops produce food year after year without needing to be re-planted, which means their root systems stay in the soil and can grow long and strong. This long root system supports the soil’s health by providing structure, preventing erosion, and successfully sequestering lots of carbon! Perennial crops also eliminate the need for annual tilling of the land, which helps to both build and maintain nutrient-rich soil. Who knew something as simple as longer roots could be such an impactful step toward a healthier future for our planet.

But Perennials Are Not The Norm

In the United States, the majority of our agriculture consists of annual monocultures. Think of expansive fields of corn, wheat and soy. According to The Land Institute, “annual crops account for roughly 70% of the human population’s food calories and the vast majority of planted croplands worldwide.” With annuals, each year, the whole plant is plucked from the ground only to be replanted via seed the following season. The current abundance of annual monocultures has led to poor soil health and ground that is susceptible to soil erosion after heavy rain or wind due to a lack of strong root systems. Additionally, since the roots are short and shallow, they can’t store much carbon, and the carbon they do store is often released back into the atmosphere when the crop is harvested and the land tilled. This constant tilling of the soil each year results in significant soil-carbon loss, soil-nutrient loss, and soil erosion. It is estimated that, as a result of these practices, we lose about 23 billion tons of fertile soil every year. That said, there are some farmers working on low-till or no-till farming methods to try and reduce this impact (but we’ll touch more on this in a future article!).

Are Perennial Substitutions Possible?

Annuals and perennials have biologically different plant anatomy. You can’t just tell a head of lettuce to “try harder” and have it survive the winter. In fact, for many plants, their short lifespan is so ingrained in their development that if you simply wait too long to harvest them, they’ll taste bad. Lettuce that isn’t harvested in time “bolts:” a process of quickly producing seeds and going bitter. Despite these biological limitations, there are ways for us humans to cultivate more perennials and prioritize soil health along the way. There are many annual plants with similar perennial relatives that could serve similar purposes for humans. This potential substitution could offer benefits for soil health, and some interesting culinary exploration too! Recently, I stumbled across a perennial grain that could replace wheat and I got Grounded-Grub-level nerdy about it.

I first read about perennial grains in a Patagonia catalog. Yes, that Patagonia—the company that makes the puffy parkas and hipster hats. But I was surprised to find articles inside on eating well, sustainable fishing practices, and perennial grains. I stopped on a page with a stunning image. It was a picture of roots, but not just any roots. Really, really long roots. Roots, I soon learned, to be of the perennial wheatgrass called Kernza®. I found myself deep diving into a perennial grain rabbit hole, and discovered Kernza is a perennial substitute for annual wheat, and is processed, and used in many of the same ways as wheat. It has been described as having a nutty, sweet flavor making it a great choice for baking and brewing.

After discovering Kernza, I began Googling everything I could about the grain and discovered The Land Institute and its many scientists and researchers working to develop perennial grains for the future. The researchers and scientists working at The Land Institute understand the potential that perennial grains hold for producing a brighter future for our planet, and have been researching and developing perennial alternatives to our annual grain staples. Kernza, the trademark name for the grain Thinopyrum intermedium, is one of their developments.

It’s so easy to get frustrated by the enormity of climate change, and the role our agricultural system plays in it. Sometimes I feel overwhelmed by how much has to be done. But when I discover pockets of people, like those fostering soil health and doing the daily work to make our future a better place, I see the power we have when we believe we can make a difference. A single idea can lead to communal action, which can result in big change. Something like buying a bag of Kernza flour might feel like such a small step towards reversing climate change, but all of our collective small steps can shake the world.