The Colonial Language of White Food Culture

We love posting recipes on Grounded Grub, in fact, they were part of the original way we thought this site could be different. We wanted to meld the science and theory of sustainability in our food system with the practice and habits of home cooking. While coming up with creative ideas for recipes to share with our audience, we’ve often come across recipes that originate in cultures outside of the US and outside of our own cultural identities. I’m German, and I really love German food, but gosh I can tell you now that if we confined the bounds of our recipes to German cuisine alone, it might get a bit monolithic. In our globalized society however, it’s not uncommon for people to connect with (and develop a love for) cuisines outside of their heritage, particularly those they’ve had special experiences with. For example, I spent a summer in India and not only loved the cuisine, but really enjoyed cooking it and incorporating Indian spice combinations into my home cooking. Lots of Indian food is traditionally vegetarian or vegan and the recipes are warm and comforting to me. It is in these cases, with food that is completely out of our ethnic or cultural identities that white food enthusiasts (such as ourselves), can quickly bring the colonial “discovery” mindset into our writing about food and sharing recipes.

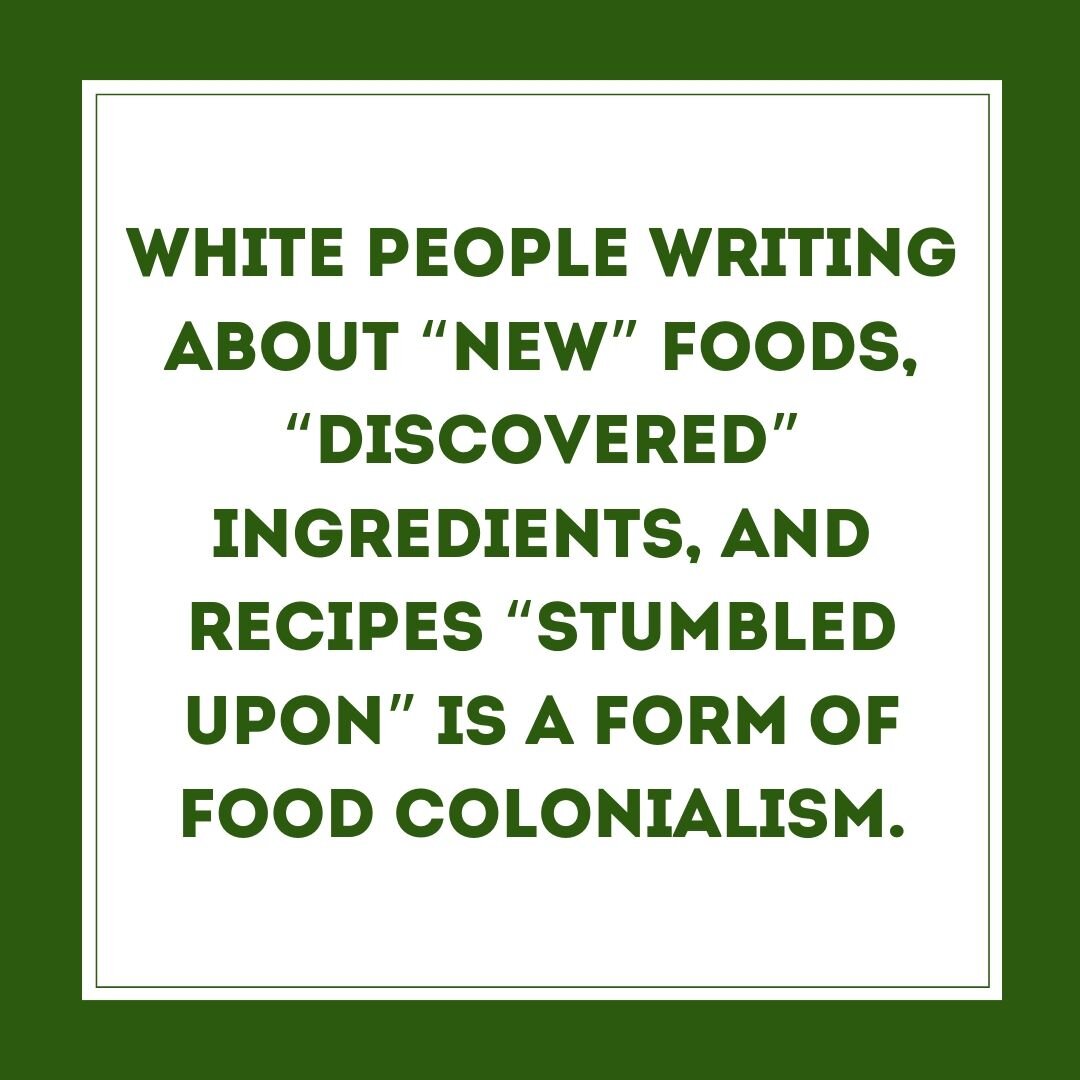

A lot of white food bloggers, nutritionists and chefs talk about “discovering” new recipes that are almost always deeply established in tradition and history. White people writing about “new” foods, “discovered” ingredients, and recipes they’ve “stumbled upon” is a form of food colonialism. Even when people cite generally where a recipe is coming from, they often center the storytelling around their experience of finding the recipe, rather than the food itself and the culture it comes from. Additionally, many of the “superfoods” that are celebrated for their “new” in the food-culture-lexicon have been eaten by indigenous people for centuries (read our Deep Dive on Superfoods for more on this). What’s more, many white nutritionists and food bloggers focused on vegetarianism and veganism separate these foods even further from their roots by reworking traditional recipes to make them “clean” or “better” (read about the racism in the “clean” eating movement in a recent article here).

In “Decolonize Your Diet: Notes Towards Decolonization” by Catrióna Rueda Esquibel, Catrióna writes about how the Mediterranean Diet is often hailed as the “healthiest” by western nutritionists who typicallydisregard the high nutritional value of traditional foods in other cultures. Many of those traditional diets have changed over time with the introduction of new foods brought in by the globalized industrial food system (often paired with a reduction in access of native foods that have become unaffordable due to global demand), or have vastly changed when brought out of their traditional food system:

“Instead of taking chocolate or berries or coffee or bananas out of one cultural context and placing it in another for profit, we should instead recognize and respect the cultural contexts that our foods come from: who ate them and why? What were traditional ways of preparing it? How were they supplemented or complemented by other foods? “

(Read the full piece here.)

Food colonization can happen on massive scales and often colonizer countries have come to deeply identify with foods of the colonized. Namely, after colonizing India, the UK has literally adopted the culture to the extent that “curry” is their national dish, and there are many dishes that are considered “iconic” Indian food that are a result of colonization—like the popular chicken tikki masala.

For a deep history on the connection between food and colonialism we highly recommend reading the full piece, “Food, Colonialism and the Practice of Eating” by Dr. Linda Alvarez of The Food Empowerment Project (read the full article here):

“Colonization is a violent process that fundamentally alters the ways of life of the colonized. Food has always been a fundamental tool in the process of colonization. Through food, social and cultural norms are conveyed, and also violated... Understanding the history of food and eating practices in different contexts can help us understand that the practice of eating is inherently complex. Food choices are influenced and constrained by cultural values and are an important part of the construction and maintenance of social identity. In that sense, food has never merely been about the simple act of pleasurable consumption—food is history, it is culturally transmitted, it is identity. Food is power.”

Food is a deeply personal experience and is one of the primary ways most cultures come together (read “On Carrot Eggs” a reflection on food as his connection to his Taiwanese and Jewish identities from contributor Josh Sadinsky). Enjoying food from around the world can expand our understanding of different people and cultures and allow us to connect with them on a deeper level. However, we must be aware that appreciating a cuisine and co-opting it for our benefit are completely different things. What can we all do to help this cause? Support restaurants and businesses owned and operated by people from those cultures, tip them well, and spread the word of how delicious their food is. Also, avoid restaurants, cookbooks and food accounts that are owned and run by white people that co-opt cultural and ethnic cuisines and ignore the rich history and tradition behind them.So what can you do when you find a recipe that is new to you?

Are you directly taking a recipe from someone else? Give them credit. Link to their recipe. Acknowledge the work that they do to communicate their cultural traditions with broader audiences and don’t confuse their efforts with your own.

Bounty at a summer market in Pharenda, Uttar Pradesh, India.

You can give credit to the culture that the food came from: “I have been learning more about Cuban history lately and this Picadillo recipe has been part of that—it’s delicious! I found it in this cookbook—wanna borrow it?”

Rather than saying you “put an exciting twist” on a recipe, you can speak to ingredients available in your area or your pantry: “I was making this recipe but didn’t have access to the traditional ingredients because I live in a rural area, I decided to use butternut squash instead of the traditional squash the recipe calls for.”

Disclaimer: We haven’t always done a perfect job with this. In fact, we’re going through a lot of our old recipes to make sure our language fully acknowledges the deep roots that come with different cultural foods. We are also making a commitment moving forward to be both sensitive and transparent about how we are sourcing recipes, and try to bring in as many voices outside of our own to share recipes from their own cultures. We are currently in the process of developing financial support systems so we can pay BIPOC contributors for their work, rather than continuing to ask for free contributions to this site. We look forward to growing this platform in an equitable way as a community.