The Cold Chain

Food Waste

When learning about ways to reduce the footprint of our food system on the planet, reducing waste is always up there on the list. From plastic waste, to long transport lines, to not making the most of food itself, our system can be wasteful at nearly every level. Personally, I’ve always found individual food waste to be particularly devastating because it feels so easily avoidable and seems disrespectful of the people at all levels of the food system who have put so much time, energy and resources into these foods that were then carelessly thrown away. I’ve become determined to make the most of every food-scrap in my home cooking (which has actually been a really fun challenge and a beautiful learning experience). However, in our fight to reduce food waste, we have to remember that not all food waste happens in our kitchens, and not all countries experience food waste for the same reasons. Infrastructure investment and access to various technologies can dramatically affect how different populations are able to grow, process and store food. But before we get into that, let’s get a slightly better understanding of what food waste is, how it happens, and why.

How much food do we waste?

While there is notable variation in the data at both global and national scales, current estimates indicate that nearly one third of the entire food produced for our consumption is lost or wasted during its life in the food supply chain (14).

Why do we waste food and where is it wasted?

There are actually two different categories of food waste that refer to different parts of the food chain. Food loss (which, as a definition, varies through time and across borders) occurs at all stages along the food supply chain. In high-income or developed nations, the majority of food waste occurs due to the practices/behaviors of retailers and consumers. With food waste, in this context, defined as food wasted by consumers/retailers, data from the Food and Agricultural Organization of the UN indicates that much more food (as much as nearly 20 times greater) is wasted on a per-capita basis in developed nations than in developing nations. This takes form in things like “quality control” (discarding food that doesn’t meet visual standards or that has been on the shelves longer than a predetermined date, which can result in nearly 40-50% of retail-food being needlessly discarded), damaging in handling, and/or simply being left to spoil (14). However, in economically-developing nations, the vast majority of food loss occurs at an earlier stage of the food supply chain.

What factors into waste prevalence?

In economically developing nations, food is predominantly lost due to inefficient harvesting processes, inadequate storage facilities, and a lack of infrastructure (14). Not only is the infrastructure often inadequate to handle and maintain the freshness of this food, but the environmental conditions in which these processes occur are often, in the case of developing nations, particularly harsh on these systems. Many of these nations host climates that are particularly hot and humid. Food left in storage facilities and vehicles that are not temperature controlled may likely experience high enough temperatures that natural degradation will

occur rapidly. In fact, most of these processes double their rate with each increase of 10ºC. This degradation can lead to a loss of color, flavor, nutritional value, as well as changes in texture (4). In addition to natural degradation leading to food which may be considered less desirable, this degradation is often paired with an increase in the presence of microorganisms which can yield food not just undesirable, but unsafe.

What is the cold chain?

This is where the cold chain comes in. The cold chain is the system of temperature-controlled transportation and storage that allows agricultural products to move from the farm to the grocery store in a way that preserves their quality all along their journey. In short, in order to preserve the freshness, safety, and desirability of food, a network of refrigeration, storage, and transportation systems are required to get the food from producers to grocery stores as quickly and safely as possible. Each component of the cold chain, as the name suggests, keeps food within cooled conditions to reduce the rate at which internal and external changes (including degradation and microbial growth) occur.

What are the necessary components of the cold chain?

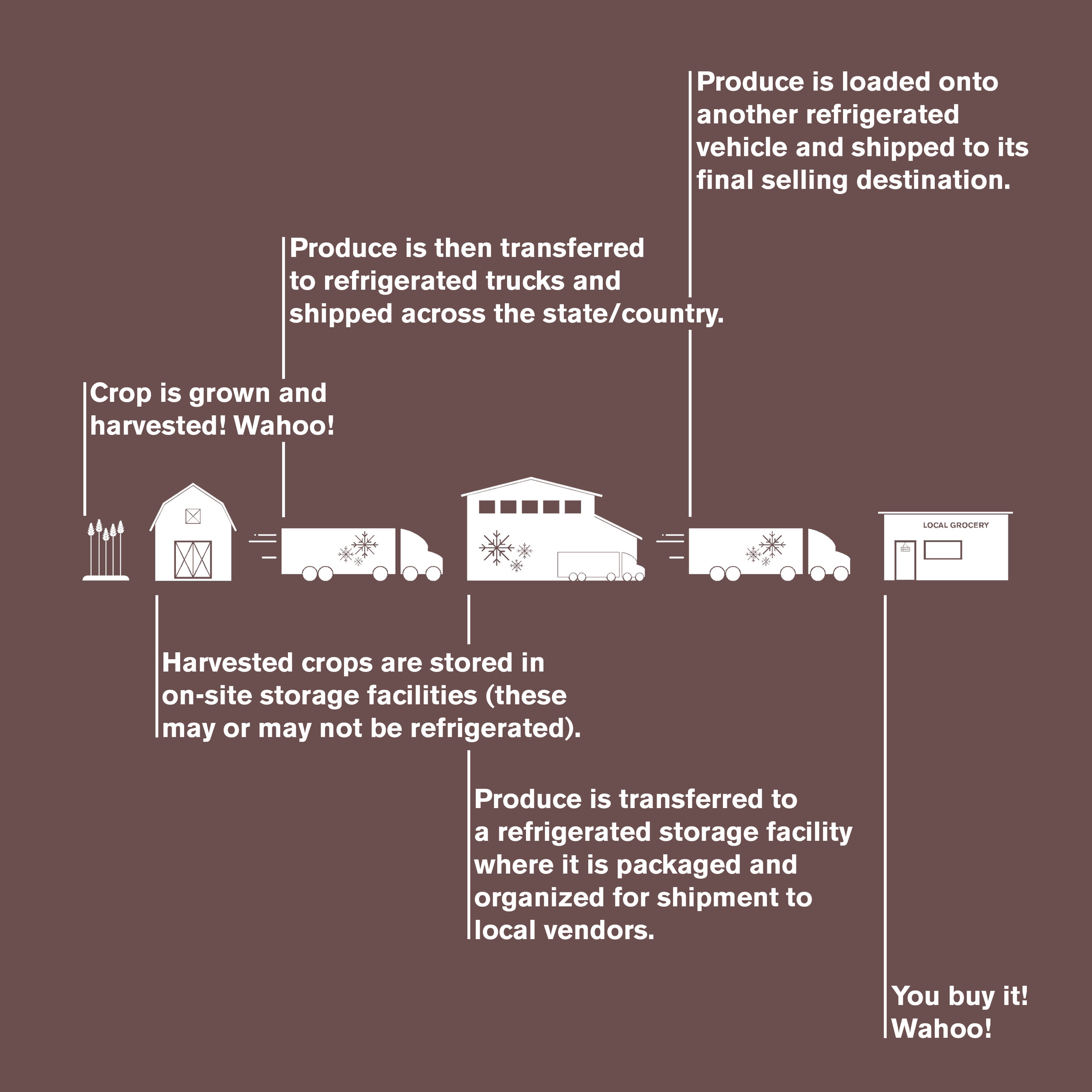

As previously mentioned, the cold chain contains a number of constituents which all play a role in the transportation and preservation of these goods. A simplified cold chain network could appear as follows:

Food harvested by producers and moved to storage facilities that control internal conditions either by powerful HVAC (heating, cooling and ventilation) systems, or by the use of refrigeration units. The form of this component is highly dependent on the type of food being produced and the nature of the producer. For example, potato farmers may require substantially less infrastructure to regulate acceptable storage conditions than would the producers of more delicate produce like lettuce or cabbage.

This food is then packaged and transferred to a transportation vehicle that (almost certainly) includes internal refrigeration units.“It is estimated that there are approximately 1300 specialised refrigerated cargo ships, 80,000 refrigerated railcars, 650,000 refrigerated containers and 1.2 million refrigerated trucks in use worldwide (Heap, 2006)” (12).

This food is then unloaded at a secondary storage facility where it is likely refrigerated. Like producers, these warehouses are often specialized for storage of particular types of food, and thus, the infrastructure they require to adequately regular required conditions varies.

The food is then transported again, via transportation vehicles (that almost certainly include refrigeration units), to retailers (grocery stores) where it is available for sale (with or without continued refrigeration). “In 2002 it was estimated that there were 322,000 supermarkets and 18,000 hypermarkets worldwide and that the refrigeration equipment in these supermarkets used on average 35–50% of the total energy consumed in these supermarkets (United Nations Environment Programme, 2002)” (12).

Who owns/pays for the cold chain?

Different elements of the cold chain are typically owned by different players in the food supply chain. For example, the producer likely owns their own on-site holding facility—which is in their interest as they want to be able to sell as much of the produce they poured time and resources into as possible. A middle-man distributor may own the transportation vehicles and secondary storage facility—which they will be incentivized to keep effective and efficient as their income is related to the amount of product they're able to transport and store for sale. And finally, the retailer may own the secondary transportation vehicles—which they will be incentivized to keep effective and efficient as they want to preserve as much of the food that they have bought for consumer sale. That being said, depending on the scale of each of these constituents, costs for the systems may (and in many cases in developing nations, do) outweigh the loss in sales from letting food go to waste. Most cold chain technology is developed in high-income countries and is sold for profit around the world, making the cost exceedingly high for most citizens of low-income countries. Accordingly, it can often be the responsibility of larger powers like our governments and big corporations to ensure that, for the sake of the environment and our host of food-related social issues, cold chain systems are created where absent and maintained or expanded where present.

Governments looking to invest in public/private sectors in an effort to meet carbon mitigation goals may see the cold chain as an opportunity

As urban populations continue to grow disproportionately faster than the overall global population, and as leadership at national levels continues to be ineffective in its effort to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions, city governments around the globe are increasingly being called upon to address global climate change. In their efforts to do so, these governments often set emission reduction goals, which can be satisfied by any number of initiatives.

It is often the case that emission mitigation strategies/initiatives enacted by city governments are “felt” beyond their city borders. While things like air and water quality improvement as a result of emission reductions can be directly “felt” by city residents, much of impacts of emission reductions are “felt” at a global scale. Accordingly, if city governments are interested in their investment dollar yielding as great an impact as possible on emission reductions at a global scale, it may be in their best interest to look beyond their border for places to invest.

As previously mentioned, the vast majority of food lost in developing countries is lost during the storage and transport portions of the food supply chain. These nations are also often the hosts of harsh climates (which exacerbate the detrimental conditions that make the cold chain so necessary), and the most likely to be void of the necessary infrastructure to support cold chain systems/networks. Furthermore, the city governments within these nations often are particularly resource restricted, and may likely have more pressing and urgent issues in their purview. Accordingly, this current gap between supply and demand of cold chain networks may present an opportunity to other international governments looking to enact emission mitigation initiatives in new and innovative forms. By this we mean that as governments in economically-developed nations search for ways to reduce the footprint their nations/states/cities have on our planet, viewing aid toward other nations as a viable strategy that can be immensely fruitful in ways beyond only emission mitigation should be heavily considered.

Why the cold chain is worth investing in

The cold chain presents a potentially far reaching and unique opportunity to city governments in these situations. An investment in the cold chain has the potential to reduce carbon emissions and resource consumption from agriculture, food retail, and waste management sectors, as well as helping combat global food shortages in the locations that are often most heavily burdened by these issues.

Does the cold chain expend more emissions than it saves?

While the cold chain presents an opportunity to address a variety of important issues, both in the environment and in our food systems, they consist of some particularly energy intensive and high-emission-producing technologies (including refrigeration units and vehicles such as trucks, trains, planes, and ships). Accordingly, if cities wish to invest in these systems at an international scale for the purpose of emission mitigation, it is worth exploring a comparison of emissions produced by cold chain systems and emissions saved by their operation.

The BIO Intelligence Service has estimated that there is a roughly 1:10 ratio of emissions spent on cold chain constituents and emissions saved from food loss. Furthermore, The Global Food Cold Chain Council estimates that for practical purposes, without advancements in operational and technological efficiencies, we can currently only consider a roughly 60% reduction in food loss as a feasible goal (surmised from current performance of cold chain systems in highly developed nations with ample infrastructure to support them).

Accordingly, it can best be estimated that between 802 million and 560 million metric tonnes of greenhouse gases emissions can be saved by reductions in food loss, at the cost of roughly 80 and 56 million added metric tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions (respectively) due to the added cold chain infrastructure.

This translates to roughly 722 million and 504 million metric tonnes of greenhouse gasses reduced from current annual global emissions.

To put that in perspective that would be like eliminating the entirety of the annual GHG emissions from Canada (1).

Investment in cold chain technologies, particularly in developing nations, is, at the very least, a feasible approach to carbon mitigation. As previously shown, for every additional unit of CO2 emitted by the constituents of these systems (be them due to refrigeration units or the fuel for transportation vehicles), approximately 10 units of CO2 will be eliminated from annual emissions directly associated with food-loss. It is however worth mentioning that these positive impacts are incredibly conservative in the scope of food loss.

Food loss and the cold chain not only impact avoidable emissions to our atmosphere, but can heavily impact a host of other issues:

Natural and Agricultural Resources

Natural and agricultural resources including water, land, fertilizers, seeds, and a variety of other inputs, are becoming more scarce and costly, and food loss/waste is in turn a waste of these precious resources as well (4). “The production of this lost and wasted food globally has been estimated to account for 24 percent of total freshwater resources used in food production, 23 percent of global cropland, and 23 percent of global fertilizer use (Kummu et al., 2012)”(13). Additionally, “Land use changes resulting from agriculture can result in biodiversity loss, natural ecosystem loss, and overall ecological degradation (Pretty et al., 2005)“ (13).

World Hunger

Over 800 million people across the globe suffer from hunger. If we were to even halve the amount of food wasted in places like Europe and North America alone, we could feed this people 1.5 times over (14).

Waste Management Systems

“Nationwide assessments indicate that food waste, at more than one-fifth of all waste by weight, is the single largest component of municipal solid waste disposed in landfills or incinerators” (16).

Jobs

“Producers would benefit as the agricultural value chains for their food products are fully developed, and new jobs would be formed all along the cold chain for those perishable foods for which pre-cooling, cold handling, freezing, cold storage and refrigerated distribution and marketing have been demonstrated to be cost effective” (4).

It should also be mentioned that investments in cold chain system creation or expansion are often not without challenges, especially in many developing nations. These challenges, many of which were previously mentioned, include harsh agro-climatic conditions (high temperatures and humidity), limited access to required infrastructure and utilities (water, electricity, roads), as well as access to other required resources like the necessary equipment, workforce, and training (4).

Moving Forward

As federal, state, and city governments across the globe pursue plans toward greenhouse gas emission reductions, we believe investment in international cold chain infrastructure/technology offers a unique opportunity.

Not only has this investment shown to significantly reduce emissions related to food waste and resource consumption, but it has the opportunity to fight global hunger and conserve our natural resources.

Climate change is a global issue, and if governments with large budgets have the ability to not only reduce global emissions, but also aid other countries in their efforts to fight hunger and thus improve economic mobility, we think it’s a win-win.

Take this opportunity to reflect on your access to this infrastructure and these technologies, and how they impact your daily life. Consider this global inequity (and its associated impacts) as you source your food, manage your waste, and decide what kinds of business/politicians/policies you choose to support.

References

1. Hoornweg, Daniel. Cities’ Contribution to Climate Change. World Bank, 2011, pp. 1–19, Cities’ Contribution to Climate Change.

2. Rodrigue, Jean-Paul, and Theo Notteboom. Transportgeography.org. 2020, Transportgeography.org, transportgeography.org/?page_id=6585.

3. Shashi, et al. “The Identification of Key Success Factors in Sustainable Cold Chain Management: Insights from the Indian Food Industry.” Journal of Operations and Supply Chain Management, vol. 9, no. 2, 2017, p. 1., doi:10.12660/joscmv9n2p1-16.

4. Kitinoja, Lisa. “Use of Cold Chains for Reducing Food Losses in Developing Countries.” PEF White Paper, vol. 13, no. 3, Dec. 2013, pp. 1–16.

5. Mugica, Yerina, and Terra Rose. TACKLING FOOD WASTE IN CITIES: A POLICY AND PROGRAM TOOLKIT. NRDC, 2019, pp. 1–53, TACKLING FOOD WASTE IN CITIES: A POLICY AND PROGRAM TOOLKIT.

6. Hester, Jessica Leigh. “A Look at Urban Food Waste, by the Numbers.” Wired, Conde Nast, 2017, www.wired.com/story/just-how-much-food-do-cities-squander/.

7. Zeuli, Kimberly, and Austin Nijhuis. THE RESILIENCE OF AMERIURBAN FOOD SYSTEMS: EVIDENCE FROM FIVE CITIES. Rockefeller Foundation , 2017, pp. 1–71, THE RESILIENCE OF AMERIURBAN FOOD SYSTEMS: EVIDENCE FROM FIVE CITIES.

8. Newman, David. “Expert Voices: Improving Food Waste Management In Cities: An Opportunity to Change Our Planet for the Better.” c40.Org, 2018, www.c40.org/blog_posts/expert-voices-improving-food-waste-management-in-cities-an-opportunity-to-change-our-planet-for-the-better.

9. Adhikari, Bijaya & Barrington, Suzelle & Martinez, Jose. (2009). Urban Food Waste generation: challenges and opportunities. International Journal of Environment and Waste Management. 3. 10.1504/IJEWM.2009.024696.

10. Gogou, E., et al. “Cold Chain Database Development and Application as a Tool for the Cold Chain Management and Food Quality Evaluation.” International Journal of Refrigeration, vol. 52, 2015, pp. 109–121., doi:10.1016/j.ijrefrig.2015.01.019.

11. Montanari, R. “Cold Chain Tracking: a Managerial Perspective.” Trends in Food Science & Technology, vol. 19, no. 8, 2008, pp. 425–431., doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2008.03.009.

12. James, S.j., and C. James. “The Food Cold-Chain and Climate Change.” Food Research International, vol. 43, no. 7, 2010, pp. 1944–1956., doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2010.02.001.

13. Thyberg, Krista & Tonjes, David. (2015). Drivers of food waste and their implications for sustainable policy development. Resources Conservation and Recycling. 106. 110-123. 10.1016/j.resconrec.2015.11.016.

14. Adam, Alina (2015) : Drivers of food waste and policy responses to the issue: The role of retailers in food supply chains, Working Paper, No. 59/2015, Hochschule für Wirtschaft und Recht Berlin, Institute for International Political Economy (IPE), Berlin

15. Lipinksi, Brian. “Reducing Food Loss and Waste.” World Resource Institute: Creating a Sustainable Food Future , 2013, www.wri.org/publication/reducing-food-loss-and-waste.

16. Mandyck, John M., and Eric B. Schultz. Food Foolish: the Hidden Connection between Food Waste, Hunger and Climate Change. Carrier Corporation, 2017.

17. Intelligence Service, BIO Intelligence Service. Assessing the Potential of the Cold Chain Sector to Reduce GHG Emissions through Food Loss and Waste Reduction. 2015, Assessing the Potential of the Cold Chain Sector to Reduce GHG Emissions through Food Loss and Waste Reduction, www.foodcoldchain.org/resources/publications/.